A few nights ago, I met an old friend in a coffee shop in New Delhi. Stephane is a French architect, living and working in India for the past 15 years.

“It’s really strange in India right now, don’t you find?” he asked me. “I’ve never seen it like this. All my friends are depressed. No one has any hope. I’ve never been in a country where people were so oblivious to the concept of a common good, where they are so short-sighted, so ready to cut corners for the sake of an easier, cheaper way to do things.”

That week I had been staying at the home of my close friends Deepa and Prashant Bhushan and the mood there was anything but depressed. In fact, I had never seen the family so optimistic.

The Bhushans are one of India’s best-known family of lawyers. Shanti Bhushan, Prashant’s father, was Law Minister during the Janta Party’s government in the late 70s. Earlier, in 1975, he had successfully prosecuted Indira Gandhi for her unfair electoral practices while Prime Minister, resulting in her own election being invalidated.

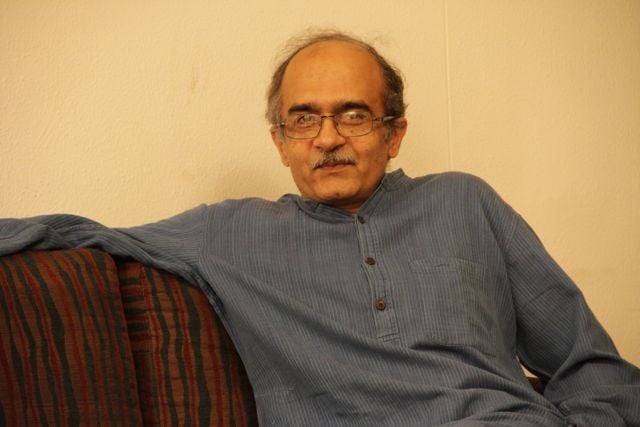

Prashant is equally well-known for his tireless efforts in public interest litigation – though of late, his primary involvement has been in the India Against Corruption movement, the Aam Aadmi (Common Man) Party it has formed and its current hectic efforts to contest in the upcoming Delhi state elections.

When the idea of contesting elections first came up, politically astute observers dismissed winning as out of the realm of possibility. Now, even the most cynical are saying – in stunned amazement – that the unthinkable may just happen. The Aam Aadmi Party’s own polls put it ahead with 47% of the vote – the ruling Congress Party polls only 22% and the rival Bhartiya Janta Party is struggling with 33%.

AAP’s symbol (with so many of India’s voters illiterate or semi-literate, symbols are crucial for ballot recognition) is a jharu – a traditional broom made of a bundle of twigs. The allocation of the symbol was random, but it could not possibly have been more appropriate: the party’s sole platform is an end to corruption in daily life and the idea of taking a broom to the murky, dusty, cobwebby world of India’s political and administrative system is appealing in a brisk, down-to-business way. The jharu offers a promise of purposeful action to a public which has been forced to put up silently with years of corruption and dysfunction so routine most have stopped even mentioning it. People just pay and get on with it, accepting the bribe as the price of getting anything accomplished.

Clearly, the Aam Aadmi Party has tapped into a huge vein of smouldering frustration. Indeed, it has been carefully cultivating it for the past two years, encouraging people to action, protest and organization. Its election campaign has been Obama-like in its strategy: the party eschews big money and expensive ad buys in favor of small, hundred rupee donations and face-to-face, door-to-door canvassing. One of its biggest constituencies, for example, is Delhi’s auto-rickshaw unions.

Rickshaw drivers are by nature and profession sympathetic to the party’s platform: they are at the mercy of predatory and corrupt police; if they don’t pay regular “protection” money, they may be fined, their licenses seized and their vehicles impounded. They are also roving ambassadors in the city. They are constantly on the move, constantly meeting new people. Their vehicles, draped with Aam Aadmi banners, are traveling billboards. They themselves proselytize for the AAP candidates and even hand out literature to their passengers.

This creative approach to campaigning is a hallmark of AAP’s style. Their appeal among educated youth is enormous, with the poor and the very poor also very much on board.

The party is known for its integrity, transparency and rigid adherence to clean politics. Yesterday it publicly withdrew support from a candidate who had not revealed the fact that he was involved in several property disputes. The faces of the party – people like Prashant Bhushan and Arvind Kejriwal (a former government bureaucrat who gave up his comfortable job for the party) – are well-known for being above reproach and dedicated to public service.

The Aam Aadmi Party benefits greatly from a sad lack of alternatives. The ruling Congress Party is saddled with the blame for an economy in free fall (the rupee is now 60 to a dollar, down from 45 to the dollar this time last year), major law and order issues, failure to deal effectively with disasters like the recent catastrophic floods in the mountain state of Uttarakhand and implicated by insinuation in just about every major scam of the past decade.

The Bhartiya Janta Party is no better except that it is the challenger. Its standard bearer is the charismatic Narendra Modi, a masterful politician whom many compare to Hitler. Openly anti-Muslim, he is believed to have engineered the massacre of over a thousand Muslims (including pregnant women whose living fetuses were torn from their bodies and decapitated) in the Gujarat riots of 2002.

When questioned about his role in the riots recently on national television, he first distanced himself from the actual events and then said off-handedly: “If we are driving a car, . . .(or) someone else is driving and we’re sitting behind, if a puppy comes under the wheel, will it be painful or not? Of course it is.” Shockingly, Modi’s appeal in many parts of the country is enormous and he is considered to be the front-runner for Prime Minister.

The one real concern for the AAP is the question of how they will govern if they do indeed win the elections. No one currently in the leadership has any experience with the day to day running even of a small town, let alone the capital of the country.

But given the basic honesty and integrity of those concerned, it seems the public may just be willing to give the AAP a chance to learn on the job.